Much of the San Diego Zoo’s history has been well documented, including Harry Wegeforth, M.D., laying the foundation for the Zoo in 1916, and the years of struggle and hard work it took to get the Zoo up and running. Not as widely known is the fact that in its second decade, Dr. Harry realized he couldn’t manage both a fledging zoo and his busy medical practice. So, he turned the operation of the Zoo over to his right-hand man—who, in this case, was a woman.

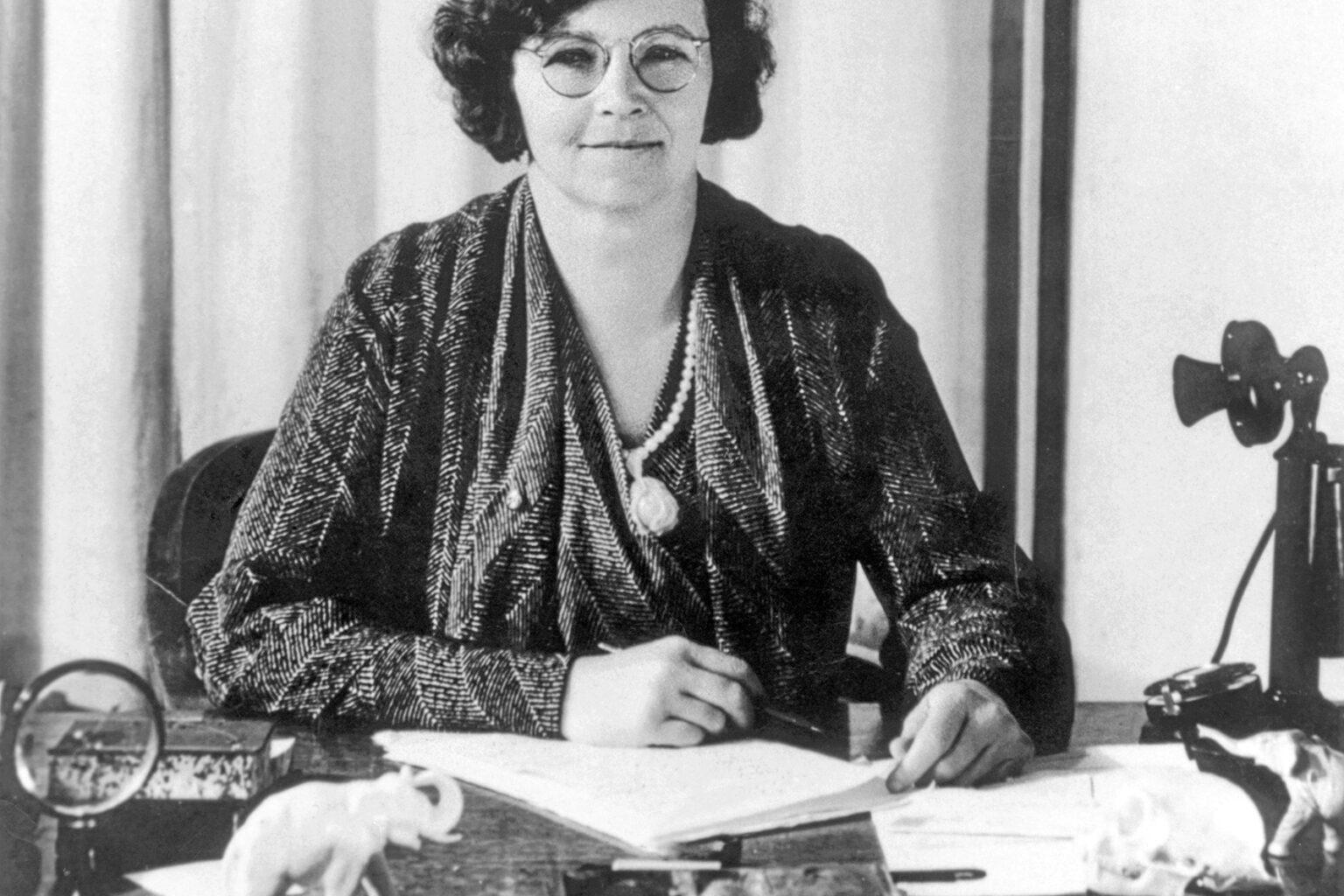

Belle Benchley had been hired in 1925 as a temporary bookkeeper, but she quickly became so much more. While putting a woman in a position of leadership may have been surprising for the times, it made sense to the good doctor. He was keenly aware that Belle had spent her lunch breaks and every spare minute familiarizing herself with the wildlife in the Zoo’s care, and with their human caretakers as well, learning as much as she could. “You might as well run the place,” Dr. Harry told her in 1927, “you’re already doing it anyway.”

Building a Foundation

During her 26 years at the San Diego Zoo, Belle Benchley became known as a champion for wildlife.

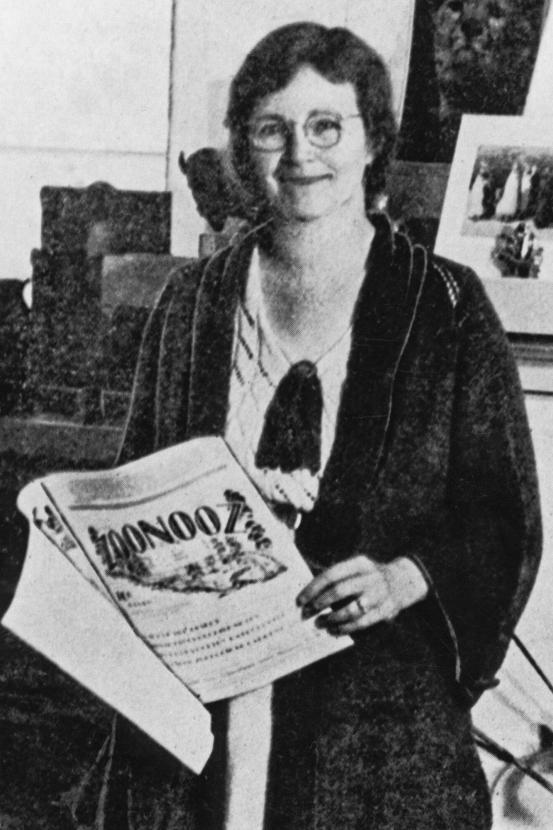

Belle was the first female zoo director in the world. Her official title was executive secretary until the 1950s, but Dr. Harry called her the “Boss” and the Zoo employees reported to her. She was also the first editor of ZOONOOZ magazine (now the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal).

She ran the Zoo’s day-to-day operations, as well as making contacts around the world to bring wildlife to San Diego. The Zoo cared for animals that had come from other facilities in Europe and Australia, but Belle wanted to expand. She learned about sailing dates for places such as Sumatra, Java, and Singapore, gathered freight rates, got on mailing lists of shipping companies, and studied regulations regarding imports and exports from each nation, aiming to establish the San Diego Zoo as what she called a “Noah’s Ark across the seas,” caring for and protecting a wide variety of wildlife species. Belle gave presentations about the Zoo and wildlife to school groups and civic organizations—anywhere she could spread the word about the Zoological Society of San Diego (now known as San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance).

But perhaps the biggest role in her 26-year San Diego Zoo career was being a champion for wildlife of all kinds. She was a driving force behind many of the Zoo’s “firsts,” including bringing gorillas here in 1931. There were only a few great apes in zoos worldwide at the time, and the arrival of Mbongo and Ngagi helped put our Zoo on the map. They made a deep and lasting impression on Belle. She called Ngagi a “perfect gorilla,” and she visited them every chance she got. Their status as cornerstones of the Zoo’s history is present even today—it’s their bronze statues that greet guests just inside the Zoo entrance.

Belle’s duties included editing the San Diego Zoo’s monthly magazine, ZOONOOZ (now the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal).

Ever mindful of the importance of instilling an interest in wildlife in future leaders, Belle started a program that used the Zoo’s tour buses to pick up children at area schools and bring them to the Zoo for an educational excursion. Eager to share her experiences with the world, Belle wrote several books, including My Life in a Man-Made Jungle, My Animal Babies, and My Friends, the Apes. Not only did she bring an understanding of the day-to-day experiences of running a zoo to the public, but she also introduced wildlife as individuals, showing that each has their own personality.

Upholding a Legacy

With Dr. Harry concentrating on his medical practice, Belle took her responsibilities to heart. She relied on her considerable organizational and interpersonal skills to keep the San Diego Zoo going. She bartered deals to keep wildlife at the Zoo fed during the Great Depression and after nationwide rationing was imposed during World War II.

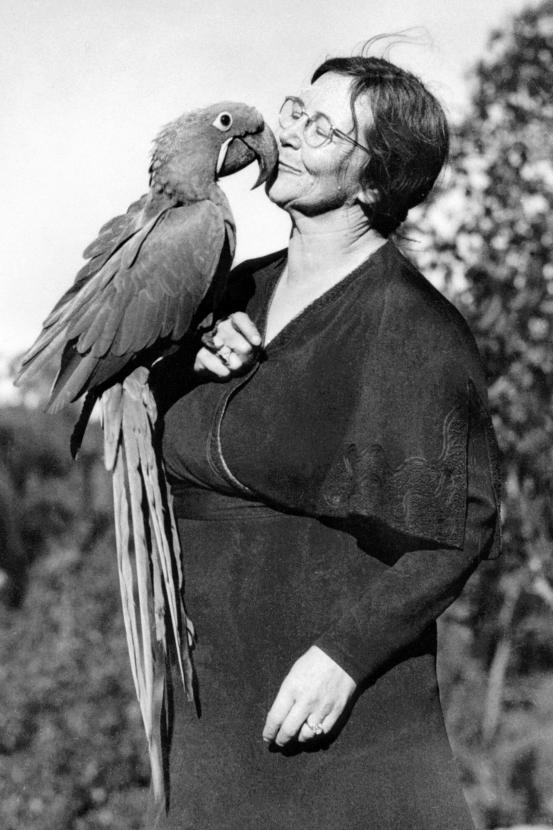

Belle was known for her hands-on care of wildlife at the Zoo, and the interest she took in each individual. She made daily excursions around the Zoo visiting Maggie the orangutan, Bum the Andean condor, and many others. Mickey the Baird’s tapir was a particular favorite, as she had arrived at the San Diego Zoo in 1934—sickly and underweight. Belle had her moved to a habitat closer to her office so that she could tend to the youngster daily. Mickey flourished and Belle continued those visits even after Mickey returned to her regular habitat.

Belle’s daily care helped Mickey the tapir thrive.

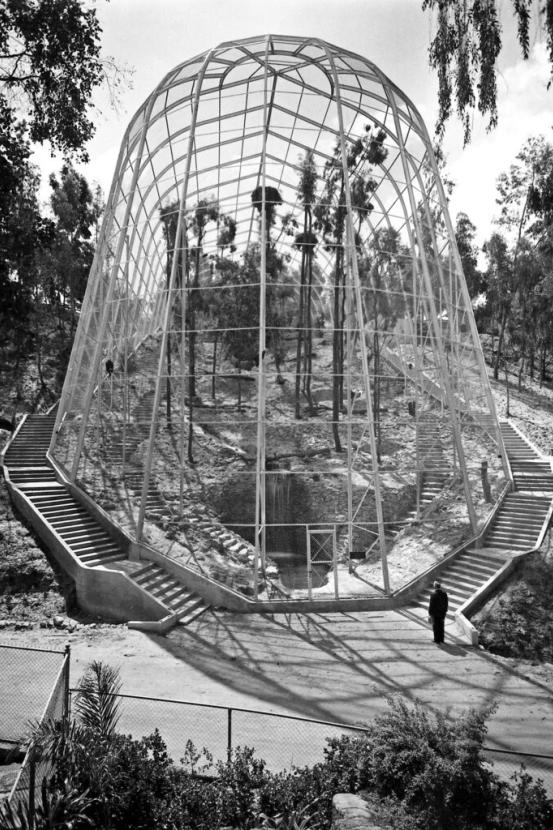

When it came to the wildlife in her care, Belle’s intuition was legendary. It was noted at Belle’s induction into the San Diego County Women’s Hall of Fame in 2007 that she could sometimes detect an animal illness before the wildlife care specialists or veterinarians, noticing when an individual “just didn’t look quite right.” She believed in creating habitats that were as comfortable as possible for the species in her care, and she consulted experts as to dietary needs and specific care requirements. She suggested the Zoo do away with cages entirely and build open-air habitats instead. Generous donors, like Ellen Browning Scripps, helped fund the improvements and new infrastructure.

Free-flight aviaries were among the innovations Belle championed. Benefactors such as Ellen Browning Scripps helped fund new facilities.

Belle used any new information she could to improve Zoo operations, and she was appreciative of anyone who helped with her quest. As she wrote in My Life in a Man-Made Jungle, she “learned from some rather trying experiences and the practical knowledge of the men employed at the Zoo, who were generous always in their help, and their support, for like Dr. Harry, they had complete understanding and enormous patience with persons who tried hard, accepted help, and were always doing their best.”

An Eye to the Future

When Dr. Harry passed away in 1941, Belle felt the loss deeply, but she forged ahead to build upon what they had started, knowing that was what Dr. Harry wanted. She continued striving to innovate and expand the concept of what a zoo could be.

A team effort: During her tenure with the San Diego Zoo, Belle worked collaboratively with a board of trustees and wildlife experts to create the future of the organization.

In 1950, the Zoo’s animal department had grown so much it needed to be divided, and she established mammal, bird, and reptile sections, with a leader for each department. They worked with the hospital department to ensure proper care; and a combined commissary and purchasing department helped with nutrition. Belle determined that “proper diets do not originate in the warehouse—they are merely procured or provided there, and the ingredients must be sorted and stored safely before being served.” Keeping everything in one central location made guarding it and maintaining inventory easier, as well as aiding in quality control.

Belle’s commitment to animals became known in countries around the world. She was widely known as the “Zoo Lady,” and was renowned as an expert in wildlife behavior and zoo strategies. Her reputation and influence led to her being elected as the first female president of the American Zoo Association—now known as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA)—in 1949. When she was ready to retire in 1953, she hand-picked her successor: Dr. Charles Schroeder, who had started at the Zoo in 1932 with a five-year stint as a veterinarian/pathologist. Belle recognized in him a fellow visionary. And she was proved right—Dr. Schroeder went on to create the San Diego Zoo Safari Park in 1972.

Belle Benchley’s love of animals, and the pride she felt in caring for them, continued even after her passing in 1973. Her headstone is adorned with the etched likeness of a gorilla. Along with her name and dates appears her favorite identifier: “The Zoo Lady.”

What drove Belle to foster her love of wildlife can be found in a quote from My Life in a Man-Made Jungle: “Now and then I meet someone who says, ‘I don’t like animals.’ I know that that person has missed the proper chance to know animals and has thus been deprived of one of the richest experiences in life. I cannot help from pitying him, for to know animals is to love them.”

Belle Benchley dedicated her life to doing both. Her influence can still be felt today, especially by those who followed in her footsteps. “Belle was an amazing woman and leader,” says Erika Kohler, the San Diego Zoo’s current executive director. “She managed the Zoo through some of the most difficult times, and she was an incredible force who helped make the Zoo what it is today. She was an inspiring woman!”