The Multi-Layered Plan to Save the Mountain Yellow-Legged Frog

It was an amphibian mystery: in the 1970s, frogs around the world began inexplicably dying. Sometimes the declines were slow and steady. In other cases, sudden and massive die-offs were documented—even in protected and pristine areas. It wasn’t until scientists from around the world gathered at the first World Congress of Herpetology in 1988 and shared similar observations that they realized something bigger was happening. But there was no clear explanation for why so many frogs were vanishing.

Mountain yellow-legged frogs have been California residents for a long time: at least 8 to 12 million years.

Global Diagnosis, Local Treatment

In 1998, a fungal pathogen—amphibian chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis—was discovered. It infects frogs’ skin, disrupting their ability to breathe through their skin and their osmoregulation (a process to maintain the osmotic pressure of fluids and electrolytic balance in their systems). Unfortunately, these disruptions have potentially fatal consequences. In combination with other threats like habitat loss, pollution, introduced predators, and climate change, this chytrid pandemic—largely spread by human movement of frogs in the food and pet trades—continues to contribute to losses of amphibians around the world, as well as here at home.

Mountain yellow-legged frogs historically inhabited montane streams and lakes (above).

One representative of this global crisis can be found nearby. The southern mountain yellow-legged frog Rana muscosa was, until recently, the most abundant amphibian in Southern California’s mountain lakes and streams. Their abundance made them a keystone predator and prey, as well as a critical agent of nutrient and energy cycling in the mountain aquatic ecosystem. The species faces many of the same threats causing amphibian declines globally—including chytrid. Currently, only a few hundred wild adults remain at only eight locations in the endangered southern segment. This is a population decline of more than 98 percent; and sadly, these frogs no longer remain in San Diego County.

Jumping Into Action

In 2006, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance got involved. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service asked our organization to participate in an emergency rescue operation. Tadpoles from a drying pool were collected and transported to our facilities, to develop care and breeding protocols. The hope was that these protocols could be used to prevent the complete loss of a last remaining, unique lineage of this species— an opportunity to save biodiversity right in our own backyard.

There are two species of mountain yellow-legged frogs: the southern mountain yellow-legged frog, and the Sierra Nevada mountain yellow-legged frog.

Since that time, our frog program has transformed into a full-scale conservation breeding and reintroduction operation, using genetic data to inform management. While tadpoles have a very low rate of survival in their native habitats, our ex situ facility can support them through metamorphosis into larger, hardier froglets. Since our first reintroduction in 2010, our interagency group has translocated more than 11,000 mountain yellow-legged frogs back into their native ranges.

Many threats have been addressed, and we have made a great deal of progress with our program. For example, trout and bullfrogs are voracious predators of these frogs and their offspring, and our partners have worked to remove and exclude these non-native species, allowing frog populations to persist—and even grow, in some locations. In collaboration with our reproductive science, wildlife nutrition, and conservation genetics teams, our research has helped us determine everything from the best diet to the importance of mate choice and brumation (hibernation in ectothermic, or cold-blooded animals) for reproductive fitness, to genetically informed management recommendations. We’ve monitored hormones, studied sperm, developed methods for assisted reproduction, and cryopreserved gametes and cell lines. We have also established pre-release environmental conditioning procedures, teaching frogs to recognize and respond to predators, and to swim and jump in running water before reintroduction. Today, we can raise large numbers of frogs in human care that are well-prepared to survive in their native habitats. This work has slowed the path to extinction, but the problem of chytrid persists, and we must surmount this obstacle to successfully recover the species.

Researchers from San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance unpack frogs from temperature-controlled containers to prepare them for reintroduction into their native habitat.

Measuring the Outcome

To evaluate the success of our efforts, our team conducts post-release monitoring, including disease surveillance. When we find frogs in native habitats, we collect a non-invasive skin swab, and we work with our Disease Investigations team to test for the presence of chytrid DNA. If we find frogs that have perished in native habitats, we bring them to our expert pathologists to conduct necropsies. Through these efforts, we have documented fatalities associated with chytrid at multiple reintroduction sites—a devastating finding for our devoted team, who cared for and raised these frogs to return to native habitats.

A skin swab is carefully and gently collected to test this mountain yellow-legged frog for the amphibian chytrid fungus.

Getting rid of the fungus in native habitats is likely unfeasible. It is present at all mountain yellow-legged frog sites in Southern California, and is often found on the skin of co-occurring amphibian species. Chytrid is even found in the water and soil. So the question isn’t how we can prevent exposure of frogs to chytrid; but rather, how can we help the frogs persist in their native habitats with chytrid?

Mountain yellow-legged frogs have a slow pace of life, and in their native habitat can sometimes remain as tadpoles for two full years or more.

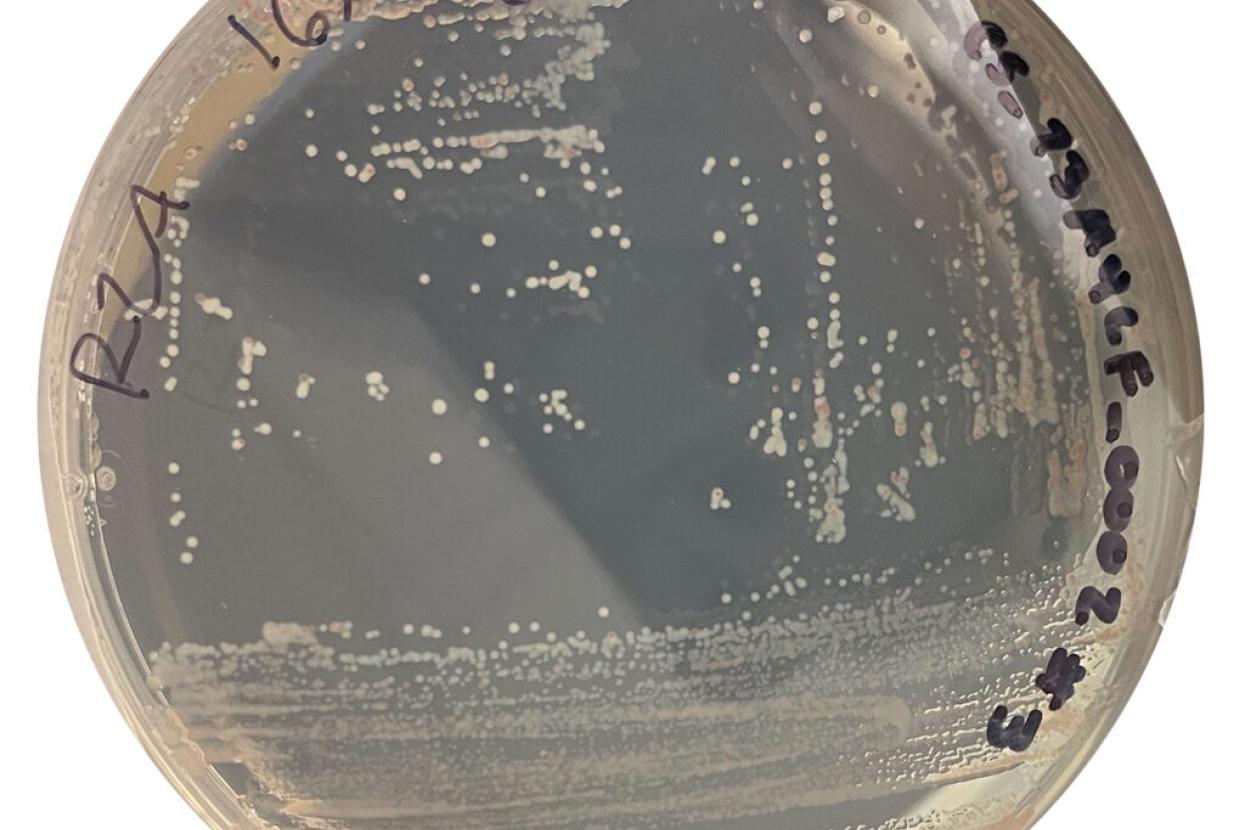

We’re starting by working toward a better understanding of the fungus itself. Last fall, our team sampled chytrid from frogs living in native habitats, and was able to successfully culture, isolate, and cryopreserve chytrid samples from multiple locations. We are working with geneticists at the University of California, Berkeley to characterize differences in chytrid across mountain yellow-legged frog sites. In coming years, we may also implement a method used in other species threatened by chytrid, which involves infecting frogs and clearing their infections before release. This strategy is thought to prepare the immune system for future exposure to the disease, similar to how a vaccination works. These experiments will also shed light on whether some populations or individuals are less susceptible to chytrid, which could point toward potential genetic management strategies.

Microbes to the Rescue

Amphibians’ skin is their first line of defense against pathogens like chytrid, and their skin microbiome is one critical component of this protection. Beneficial microbes can make some amphibian species—including the mountain yellow-legged frog—less susceptible to chytrid. We are currently reviving cryopreserved chytrid samples to develop an anti-chytrid “probiotic,” askin microbial augmentation treatment for this species. Additionally, we have collected thousands of skin swabs from mountain yellow-legged frogs to characterize how the skin microbiome varies in frogs of different ages and in different settings (in situ vs. ex situ), and perhaps most critically, in frogs with and without chytrid infections in native habitats. Ultimately, our hope is to protect frogs from chytrid in the short-term, in order to buy them enough time to evolve resistance.

When we find frogs in native habitats, we collect a non-invasive skin swab, and we work with our Disease Investigations team to test for the presence of chytrid DNA.

The task ahead is daunting, but the case of yellow-legged frogs in the Sierra Nevada mountains is a story of hope and a blueprint for conservation success that we can use. These close relatives of mountain yellow-legged frogs in Southern California are showing signs of recovery after experiencing severe chytrid-related declines. Translocations using frogs that are thought to have evolved lower susceptibility to chytrid was a key part of the recipe for recovery in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

A Leap of Faith For the Future

In 2023, we, in partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, The Wildlands Conservancy, the U.S. Geological Survey, and other partners; reintroduced frogs to a lake site, a first for the Southern California populations.

Some may ask why we work so hard to save a frog. Apart from their important and unique role in Southern California’s at-risk aquatic ecosystems, mountain yellow-legged frogs have been California residents for a long time: at least 8 to 12 million years—roughly 30 to 50 times longer than Homo sapiens have been on the planet! Hikers and campers used to enjoy the frogs’ presence in the mountains of Southern California, and would be posting their images on social media if they were there to photograph today. In less than 100 years—an evolutionary blink of the eye— this species has been driven to the brink of extinction due to human activity.

At the same time, disease-related declines in wildlife populations and zoonotic diseases (diseases transmitted between wildlife and people) are both on the rise. By mitigating threats such as the amphibian chytrid fungus, we hope to work toward saving amphibians like the mountain yellow-legged frog, and someday, they may even be San Diego residents again.

More than 11,000 mountain yellow-legged frogs have been translocated back into their native ranges in Southern California.

Many children go through a “frog phase,” when they become fascinated by these amazing amphibians. We believe everyone should have a lifelong frog phase, caring enough to conserve them and —hopefully—one day seeing this species thrive in its native habitats once more.