Micro-cutting Through

the Rainforest Canopy

Leafcutter ants do exactly what their name says: they cut pieces out of leaves from living plants. An ant’s jaw-like mandibles are powered by strong muscles and sharp inner edges. Like a chainsaw, a leafcutter ant vibrates its body to quickly and neatly saw off pieces of plants. Each ant carries their precious piece of leaf back to the group’s underground nest, but they don’t eat these juicy morsels. They compost them.

Fungus Farmers

When an ant brings a plant piece to the nest, it hands the greenery off to another member of the colony, who takes it underground, to the colony’s subterranean fungus gardens. There, smaller ants are busy biting leaves into even smaller pieces. They lick, scrape, and tuck the tiny, chewed pieces into holes.

Leafcutter ants don’t eat leaves—in fact, they can’t digest vegetation, although worker ants get nutrition from plant sap. They eat fungus, and they grow their own. Leaves are merely food for these fungus farms. Ants pinch off a tiny piece of fungus from their well-tended, nearby fungus garden and “plant” it on new leaf compost. The fungus—which flourishes for this species of ant and nowhere else—grows into food for the ants. In fact, these underground fungus gardens are a rich food source for the growing colony. In this way, leafcutter ants turn a plentiful yet undigestible resource (fresh leaves) into an edible fungus garden.

Paige Howorth, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance curator of invertebrates, explains the complexities of this tiny ecosystem. “Above ground, the ants cut leaves to feed the symbiotic fungus—but there is a battle at hand below, with microscopic foes like parasitic mold and black yeast. A successful colony manages these threats with the help of cultivated antibiotics and nitrogen-fixing bacteria to thrive.”

What’s a fungus?

Fungi aren’t plants, which use sunlight and carbon dioxide (CO2) to create their own food in chloroplasts. Nor are they animals, which ingest food. But like animals, fungi need food to survive. They take in nutrients, not by eating them, but by absorbing them with thin-walled, threadlike structures called hyphae, which also absorb water and oxygen.

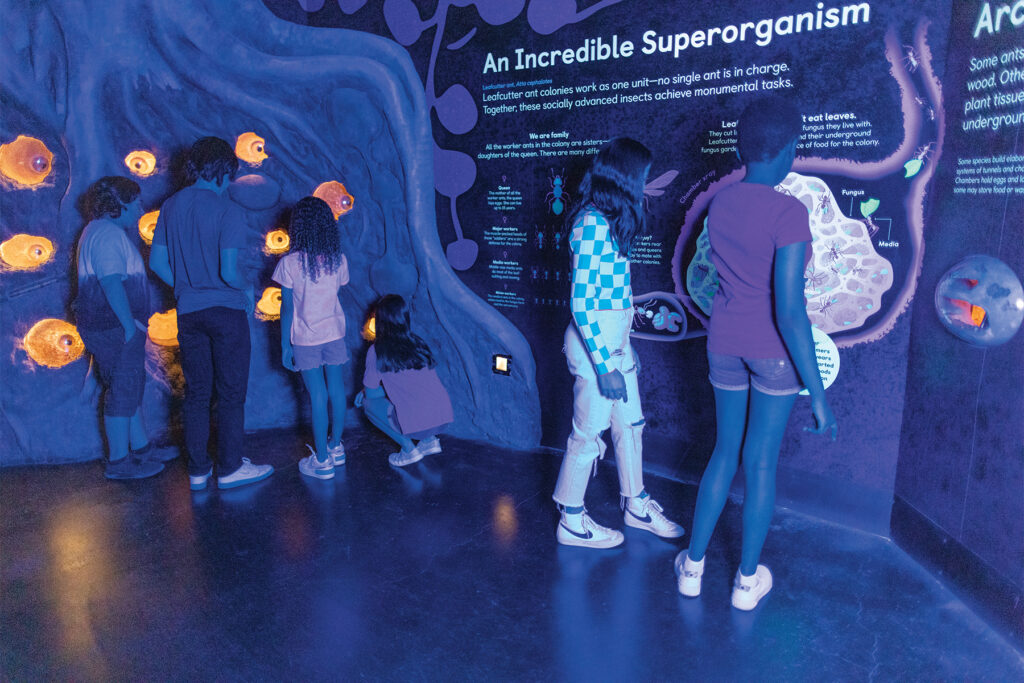

An Incredible Superorganism

How are ants able to coordinate such well-organized activity? Through instinct and complex communication that involves smell, touch, and taste, these socially advanced insects achieve some monumental tasks. That requires a whole cast of characters, including Her Royal Majesty the Queen.

A leafcutter ant colony’s queen has an important job, but it isn’t to rule her subjects. Leafcutter ant colonies work as one unit—no single ant is in charge. In fact, the queen doesn’t leave her chamber. The mother of all the worker ants in the colony, her only job is to lay fertile eggs—sometimes up to 10 million per year.

All the worker ants in the colony are sisters—daughters of the queen. Different sizes of ants do different jobs. Middle-size media workers are the harvesters that do most of the leaf finding, cutting, and carrying. When they locate leaves, they lay down a scent trail as they head back to the nest. Chemical sensors on their fellow ants’ antennae follow the scent trail to the harvesting spot and back again.

Back at the nest, major ants are soldiers that guard and defend the colony from predators. Majors—the largest ants in the colony—patrol the nest and help harvest leaves. The smallest ants in the colony, minim workers tend to the fungus farm and the ant nursery. Older minim ants sometimes ride along with the harvesters to fight off parasitic flies and wasps. Older ants of all sizes are trash collectors that protect their fellow ants and the fungus farm by removing harmful pathogens from the nest.

Where Do Babies Come From?

So, where are all these 10 million fertile eggs coming from, if an ant colony includes only a queen and her daughters—all female? Remarkably, a queen lays fertile eggs for many years using the same supply of sperm from a single wild night out (literally)—her nuptial flight. For most of the year, these eggs hatch into worker-daughters that continue the life of the colony, but seasonally, an established colony reproduces— not just single ants, but whole new colonies.

To reproduce, a colony rears offspring that are a little different than the ongoing worker-daughter output. They rear ants—both males and females—with wings. Winged ants are the only members of the colony that will ever have a chance to mate; as they are capable of producing sperm and eggs. They fly up from the nest to swarm and mate with ants from neighboring colonies, an event called the nuptial flight. Winged males are doomed to die after mating, but females that successfully mate have a destiny to fulfill.

After mating, a winged female becomes a new queen. She drops her wings, digs a chamber in the ground, and begins laying eggs. Just as importantly, she starts her own fungus farm, using a tiny wad of fungus she carried with her from her birth nest. From a single mating swarm, the queen continues to lay eggs for about 15 to 20 years. She and her fellow leafcutter ants are critical to the ecology of the rainforest. If she lives to be 20 years old, she’ll lay as many as 200 million eggs. Her colony will harvest well over 400,000 pounds of fresh plant material, and it will create several new colonies.

See leafcutter ants in action in the McKinney Family Spineless Marvels Building, in Wildlife Explorers Basecamp at the Zoo. On the top floor, you can watch them harvest and transport leaves. On the bottom floor, you can get a close look at their fungus gardens.