When we look at the history of the San Diego Zoo—especially in photos—we catch a glimpse of the organization’s forward-thinking, innovative endeavors in the world of wildlife care, horticulture, education, and conservation for which San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) is so well known today. From those modest beginnings, the Alliance—which began as the Zoological Society of San Diego—has made great strides and is now a world leader in those areas. In celebration of the 100th anniversary of documenting those achievements and milestones—first through ZOONOOZ magazine and now the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal— here are a few vignettes that take a look back at how far we have come.

A Botanical Vision for the Zoo

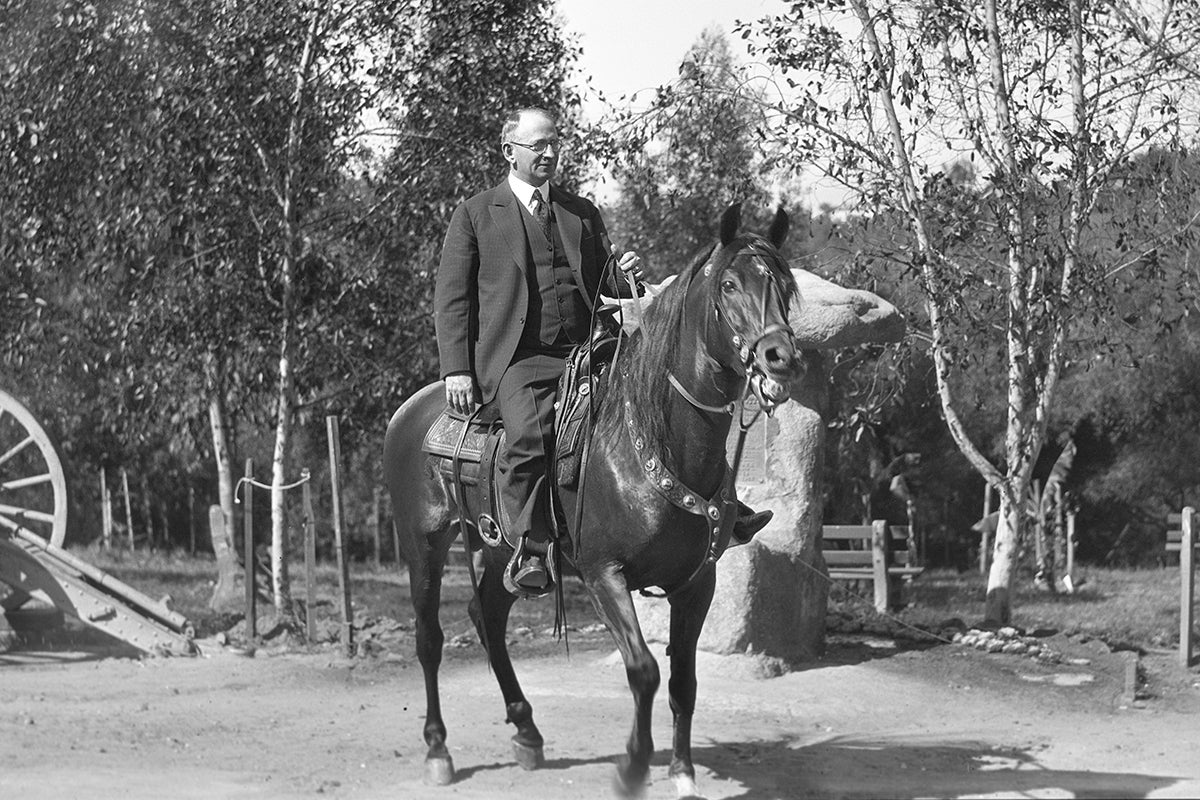

Dr. Harry Wegeforth, the visionary founder of the San Diego Zoo, had a great love and respect for wildlife but he also realized the importance of the botanical side of nature. In the early 1920s, the Zoo’s location was considered a useless tract of land with its brush-and-cactus-covered hillsides, canyons, and mesas. Dr. Harry didn’t see it that way, though—he regularly rode his Arabian stallion through the arid landscape, studying it to determine the places to build the habitats. As was noted in “It Began with a Roar,” a book that outlined the Zoo’s early years, Dr. Harry saw “the marvelous potential of the grounds, with its mesas and canyons, for development into a capacious, sylvan zoo.” In 1926, he directed his staff to plant 5,000 trees on Zoo grounds, many of them from all over the world.

Today, Dr. Harry’s botanical dream has come full circle.The San Diego Zoo and Safari Park are internationally accredited botanic gardens and Level IV arboretums. The Alliance works with partners locally and internationally to help save some of the world’s most critically endangered plants. In addition, the organization preserves seeds from San Diego County flora in the Native Plant Gene Bank. Last summer, SDZWA won a prestigious Garden of Excellence Award, presented by the American Public Gardens Association. The honor is in recognition of SDZWA’s commitment to horticulture, conservation, education, and sustainability.

In the early days of the San Diego Zoo, Dr. Charles H. Townsend (pictured above) helped Dr. Harry Wegeforth acquire tortoises.

For the Love of Turtles and Tortoises

Turtles and tortoises were among Dr. Harry’s favorite wildlife. When Dr. Charles H. Townsend, director of the New York Aquarium, visited San Diego Zoo in the 1920s, Dr. Harry said “Why is it that nobody ever gives me any turtles? Can’t you send me some turtles.” Townsend ventured on Zoo grounds to look at the turtle collection. He wanted to see what turtles and tortoises were already living in the Zoo and to assess what species he might be able to add to the mix. He was back in Dr. Harry’s office within a few minutes, laughing. “I have just visited your turtle basins—all 48 of them, you rascal. This is the biggest collection of turtles in the world!” Dr. Harry just smiled.

In 1928, Dr. Townsend embarked on an expedition to the Galápagos Islands to collect Galápagos tortoises. He wanted to save them from extinction by establishing breeding colonies in zoos and aquariums. The tortoise population had been decimated between the 17th and 19th centuries when seafaring merchants, pirates, and whalers stocked their ships with giant tortoises to use for food. Dr. Townsend acquired 180 young tortoises (estimated to be 10 to 20 years old) during the expedition—and provided the San Diego Zoo with 17 of them.

Over the years, the San Diego Zoo has hatched more than 90 Galápagos tortoises and helped fund and establish a tortoise breeding facility at the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz Island in the Galápagos Islands. In 1977, the Zoo returned Diego, an adult male Galápagos tortoise from Española Island, to a breeding program at the Research Station. Diego, who arrived in San Diego in the early 1930s, was one of only three adult male Española tortoises that were left in the world at the time. Diego fathered 800 hatchlings at the breeding facility, which has helped save that critically endangered tortoise population. Diego is still alive today! He is retired from breeding and was returned to Española Island in 2020, where he is living with many of his offspring and grand-offspring, which were also reintroduced there.

In addition, of the original tortoises that arrived at the San Diego Zoo in 1928, seven of them still reside in our Galápagos tortoise habitat on Reptile Mesa. Females Madeline, Isabell, and Chips; and males Wallace, Augustus, Oliver, and Abbot are estimated to be more than 115 years old and continue to thrive as they inspire Zoo guests.

In mid-1926, Zoological Society of San Diego Board Member Dr. Joseph H. Thompson convinced a Society donor to provide enough money to purchase two Model-T Ford buses that could ferry entire classes of schoolchildren to and from the Zoo. The buses could also be used for Zoo tours.

Model T to Master’s

In 1917, board member Dr. Joseph H. Thompson felt that the Zoological Society needed to feature educational lectures about wildlife near the habitats, and he was willing to be the lecturer. On the Saturday afternoon of the first talk, rain poured down on San Diego. Dr. Harry and Dr. Thompson were concerned that no one would show up. To their surprise and delight, 50 people, with umbrellas in hand, were standing in the rain, waiting for the lecture to begin. The talks were so successful that the Zoo began hosting nature walks and also included other natural history topics in the lectures.

For the younger audience, school groups, accompanied by teachers, traveled by streetcar to the Zoo on field trips. In San Diego schools during the 1920s, there were usually 30 children in each class but Dr. Harry noticed that only 20 children per class were visiting the Zoo. He learned that one third of the children didn’t have the money to pay for the streetcar fare. He felt it was essential for those children to experience the Zoo, too, so in mid-1926, he convinced a donor to provide enough money to purchase two Model-T Ford buses that could ferry entire classes of 30 children to and from the Zoo. And, when school wasn’t in session, the buses were used for paid tours around the Zoo, which generated extra income for the organization.

Today, more than 100 years after those first wildlife lectures, the education offerings of the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance are more comprehensive than any other zoo in the world. From the guided tours of the Zoo and Safari Park to the school groups that regularly visit each location on field trips to Summer Camp programs and youth programs such as the Conservation Corps, our education teams connect with millions of people each year. SDZWA’s Conservation Science division features teacher workshops, a conservation education lab, student field trips to conservation sites, internships, in-situ education opportunities in the countries of our conservation partners, and a one-of-a-kind Master’s Degree program in partnership with Miami University. In addition, the SDZWA Academy offers world-class training for the zoological profession via online classes.

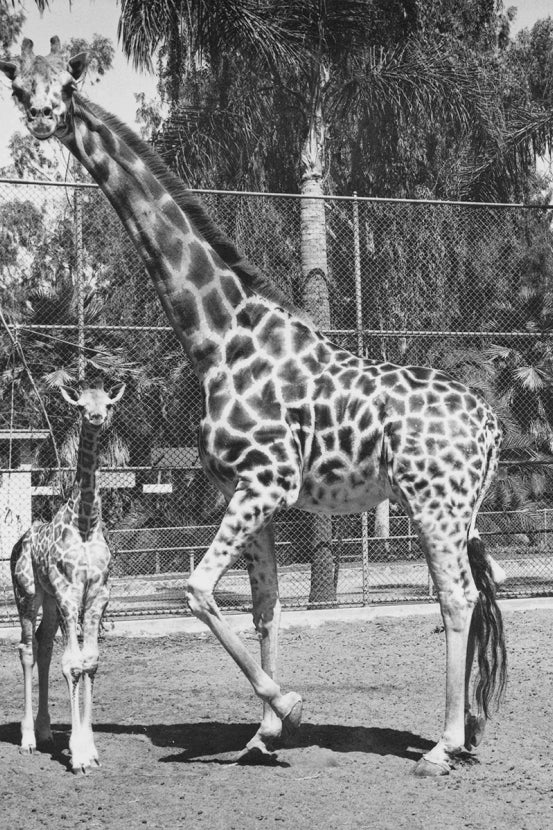

Giraffes, including an adult female named Patches (pictured above) have lived at the San Diego Zoo since 1938.

Giraffe Odyssey

Lofty and Patches, the Zoo’s first giraffes, arrived in San Diego in 1938 after an overseas adventure across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa to New York; and then a cross-country truck expedition to California. The Baringo giraffes made front page news when they landed in New York because they were considered the only giraffes to ever weather a hurricane.

Animal care specialist Charley Smith met the giraffes in New York and accompanied them to San Diego after they were quarantined in New Jersey for several weeks. They were transported in tall crates atop the bed of a truck for the 2,745-mile odyssey. ZOONOOZ editor and curator Ken Stott wrote “Newspapers in every corner of the United States followed Charley Smith and his two precious charges day by day as they made their careful journey across the continent. As the giraffes moved westward, a thousand amusing stories found their way into print and America took time to smile at the ludicrous travels of a man and two giraffes…” When Lofty and Patches finally reached San Diego, they were an instant hit with zoo goers, who immediately fell in love with them. In 1942, the Zoo’s first giraffe calf, a male named Raffy, was born to Lofty and Patches. Since Raffy’s birth, more that 250 giraffes have been born at the Zoo and Safari Park.

In 2026, Twiga Walinzi, a giraffe conservation initiative founded by the Alliance and a variety of partners, including Giraffe Conservation Foundation, Northern Rangelands Trust and Kenya Wildlife Service, will be 10 years old. Twiga Walinzi means “giraffe guards” in Swahili—and the mission is to “slow and reverse the decline of reticulated and Nubian (Rothschild’s) giraffe populations” in central and northern Kenya. A key to this initiative is working with local communities who live alongside these giraffes in more than 20 conservancies in the area.